You’ll find this avian digestive system worksheet to be an invaluable tool for understanding birds’ unique digestive processes. It covers key components like the beak, crop, proventriculus, gizzard, and intestines. You’ll learn about their specialized functions, from mechanical breakdown to nutrient absorption. The worksheet includes labeling exercises, multiple-choice questions, and a matching activity to reinforce your knowledge. You’ll also create a flow chart to visualize the food’s journey through the digestive tract. This thorough approach will help you grasp the efficiency of avian digestion and its adaptations to different diets. Immerse yourself to uncover the fascinating world of bird digestion.

Components of Avian Digestive System

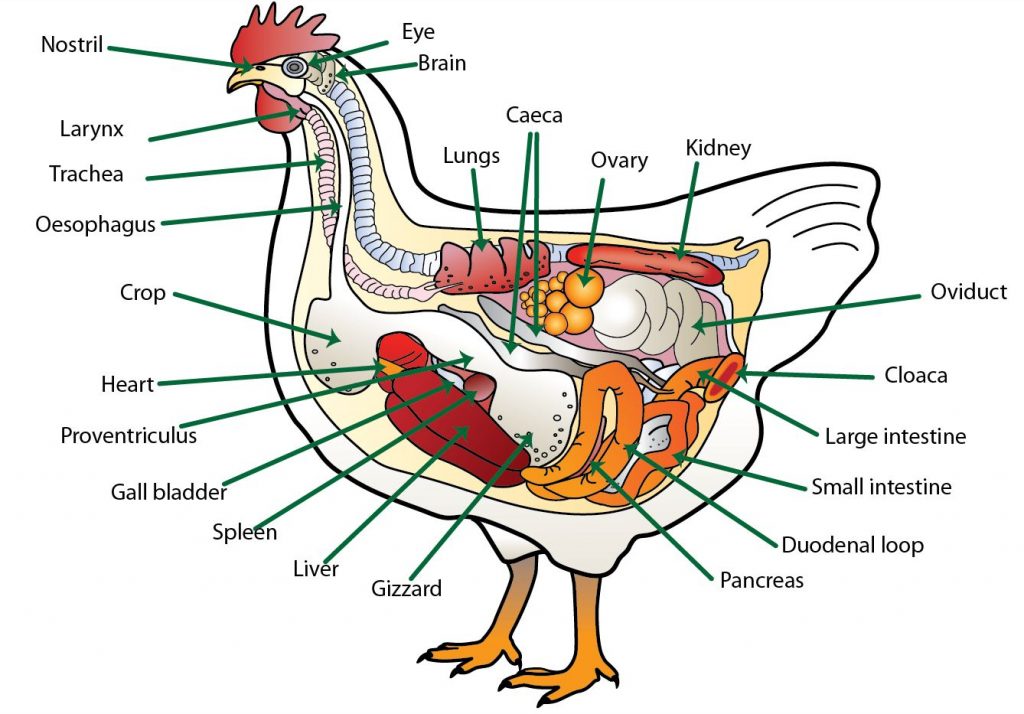

The avian digestive system consists of several specialized organs that work together to process food efficiently. You’ll find that birds have unique adaptations to their digestive system that allow them to extract nutrients quickly from their food.

The first component you’ll encounter is the beak, which birds use to capture and manipulate food. It’s adapted to each species’ diet, varying in shape and size. Next, you’ll see the esophagus, a flexible tube that connects the mouth to the crop. The crop is a muscular pouch where food is temporarily stored and softened.

As you move further down, you’ll find the proventriculus, or glandular stomach. This organ secretes digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid to begin breaking down food. The gizzard, or muscular stomach, follows. It’s a thick-walled organ containing small stones or grit that birds swallow to help grind food.

The small intestine is where most nutrient absorption occurs. It’s divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. You’ll notice the pancreas and liver nearby, which produce enzymes and bile to aid digestion.

Next, you’ll encounter the ceca, a pair of blind-ended sacs that help with water absorption and fermentation of plant material in some species. The large intestine, though shorter than in mammals, absorbs water and electrolytes. Finally, you’ll reach the cloaca, a common chamber where the digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts converge before waste is expelled.

Beak and Oral Cavity

At the entrance of the avian digestive system, you’ll find the beak and oral cavity. The beak, a unique feature of birds, serves multiple functions beyond just food intake. It’s a versatile tool used for preening, nest-building, defense, and courtship displays. The beak’s shape and size vary greatly among species, reflecting their dietary adaptations. For instance, you’ll notice seed-eaters have short, sturdy beaks, while nectar-feeders possess long, thin ones.

Inside the beak, you’ll find the oral cavity. Unlike mammals, birds don’t have teeth. Instead, they rely on their beak to manipulate food. The tongue, typically small and triangular, helps move food towards the throat. In some species, you’ll observe specialized tongues adapted for specific feeding habits, such as the brush-like tongue of nectar-feeding birds.

The roof of the mouth contains the choana, a slit connecting the oral and nasal cavities. This feature allows birds to breathe while holding food in their beaks. You’ll also find salivary glands in the oral cavity, which produce saliva to lubricate food and initiate digestion.

As you examine the oral cavity, you’ll notice the lack of a soft palate. This absence means birds can’t create suction for drinking. Instead, they must rely on gravity, tilting their heads back to swallow water. The oral cavity leads directly to the esophagus, where food begins its journey through the rest of the digestive system.

Esophagus and Crop Functions

Moving down the avian digestive tract, you’ll encounter the esophagus and crop. The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the mouth to the stomach, transporting food and water. In birds, it’s particularly flexible and expandable, allowing them to swallow large food items whole.

As food travels down the esophagus, it reaches the crop, a unique avian adaptation. The crop is an expandable pouch located at the base of the neck, serving as a temporary food storage area. It’s especially useful for birds that need to quickly ingest large amounts of food before retreating to a safer location to digest.

The crop’s primary functions include:

- Food storage: It allows birds to consume more food than their stomach can immediately process.

- Food softening: The crop’s moist environment begins to soften food, aiding digestion.

- Regurgitation: Some birds use the crop to store food for their young, regurgitating it later.

- Fermentation: In some species, the crop hosts beneficial bacteria that help break down plant material.

You’ll find that the crop’s size and importance vary among bird species. For example, seed-eating birds typically have well-developed crops, while birds of prey may have smaller or less prominent ones.

The esophagus and crop work together to regulate food intake and begin the digestive process. They guarantee that food is properly prepared before entering the stomach, where more intense chemical digestion occurs. Understanding these structures helps you appreciate the efficiency of the avian digestive system.

Stomach and Gizzard Mechanics

Birds’ stomachs and gizzards form a powerful digestive duo. Unlike mammals, birds have a two-part stomach system that efficiently breaks down food. The first part, called the proventriculus or glandular stomach, secretes digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid to begin chemical digestion.

As food moves into the second part, the gizzard or muscular stomach, mechanical digestion takes over. The gizzard’s thick, muscular walls contract rhythmically, grinding food particles against small stones or grit that birds intentionally swallow. These stones, known as gastroliths, act like teeth to crush and grind food into smaller pieces.

You’ll find that the gizzard’s strength varies among bird species, depending on their diet. Seed-eating birds have particularly strong gizzards to break down tough seed coats, while carnivorous birds have relatively weaker ones. In some species, the gizzard can even crush small bones.

The gizzard’s grinding action is essential for birds since they lack teeth. It allows them to extract the most nutrients from their food, especially from hard-to-digest plant matter. Once food is sufficiently ground, it passes into the small intestine for further digestion and nutrient absorption.

You should note that the stomach and gizzard work together to regulate food flow. The proventriculus can hold food temporarily, releasing it gradually into the gizzard for effective grinding. This process guarantees that nutrients are extracted efficiently, supporting birds’ high-energy lifestyles and diverse dietary needs.

Intestinal Absorption Process

The intestinal absorption process in birds is a marvel of efficiency. As food moves from the gizzard into the small intestine, it encounters a highly specialized environment designed to extract maximum nutrients. You’ll find that the avian small intestine is relatively short compared to mammals, but it’s incredibly effective at its job.

In the duodenum, the first section of the small intestine, bile from the liver and enzymes from the pancreas mix with the partially digested food. These secretions break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates into smaller molecules. As you move along the intestine, you’ll notice that the inner surface is lined with tiny, finger-like projections called villi. These structures dramatically increase the surface area for absorption.

Within each villus, you’ll find even smaller structures called microvilli, which further enhance absorption capacity. Nutrients are absorbed through these structures into the bloodstream. Carbohydrates are broken down into simple sugars, proteins into amino acids, and fats into fatty acids and glycerol.

You’ll observe that birds have two ceca, small pouch-like structures at the junction of the small and large intestines. These play a significant role in water absorption and the fermentation of undigested plant material. The large intestine, though short, is responsible for final water absorption.

It’s important to note that the efficiency of this process allows birds to maintain their high metabolic rates and energy demands. The rapid transit time of food through the avian digestive system, combined with the highly efficient absorption process, guarantees that birds can extract the maximum nutrition from their food in the shortest possible time.

Worksheet

Erzsebet Frey (Eli Frey) is an ecologist and online entrepreneur with a Master of Science in Ecology from the University of Belgrade. Originally from Serbia, she has lived in Sri Lanka since 2017. Eli has worked internationally in countries like Oman, Brazil, Germany, and Sri Lanka. In 2018, she expanded into SEO and blogging, completing courses from UC Davis and Edinburgh. Eli has founded multiple websites focused on biology, ecology, environmental science, sustainable and simple living, and outdoor activities. She enjoys creating nature and simple living videos on YouTube and participates in speleology, diving, and hiking.